Nowadays, not a lot of people are well aware of where their food comes from. And while we generally know they’re produced by farmers, there’s nothing else beyond that. Christine McKay talks to Bob Quinn, an organic farmer and president of Quinn Farm and Ranch and Kamut International, about the ripple effect of going against nature especially when it comes to farming and how we produce the food we eat. He touches on the importance of knowing the difference between conventional agriculture and chemical agriculture that produces cheap food that feels you up but doesn’t feed your body the nutrients it needs.

—

Watch the episode here:

Listen to the podcast here

Growing With The Grain: You Can’t Negotiate With Mother Nature With Bob Quinn

Welcome back to another episode. I am so excited to have you here with us where we work with you and help you, the small and mid-sized business owner, founder, executive to elevate your negotiations. We are all about helping you find ways to level the playing field. We do that by bringing you fascinating guests who share incredibly rich stories of their experiences, their successes, their trials and tribulations at the negotiation table. I have been so anxious and excited for this guest. I didn’t have a lot of heroes growing up when I was a kid. I grew up in North Central Montana, a very small community of about 500 to 600 people. Mr. Bob Quinn was one of my heroes and he is our guest.

I’m going to tell you from the heart what I remember of Bob. He’s the pioneer of organic farming in our entire area. When organic farming was becoming a thing and started hearing it from people who talk about natural food and not using pesticides. Bob took that on and he figured that out and it became important. It became a mission and he started seeing things in the agricultural industry. Based on his background at UC Davis where he got his PhD and some of the things he saw there then troubled him. He decided to do something about it. Bob is a man that when he decides to do something, let’s just say it gets done. He was also the father of wind farming in Montana. He was the first person to put a wind farm in the state. He was part of the original group, the total OG for all my Millennials, the OG in terms of developing the standards for what defines organic foods in the United States. He worked with the US Department of Agriculture to establish those criteria.

He has done everything from figuring out how to make wonderful, productive and amazing opportunities for wheat called Kamut, which is an ancient grain. It’s a high protein, very low gluten. He has got markets all over the world. His big market for that product was in Italy. He has been to Mongolia. He has been everywhere. Coming from our little town of 550 people where we have had some notoriety. One of the Senators is from our state and if you like his politics, that’s great. If not, that’s fine too. The bass guitarist and cofounder of Pearl Jam’s from our hometown of Big Sandy Montana. Bob Quinn, my hero is from there, too. Bob, thank you so much for being here. I’m excited to have you here.

It’s a great honor for me to be here and to hear all that. Sometimes you don’t know what influence do you have when kids are growing up around you. That was very kind.

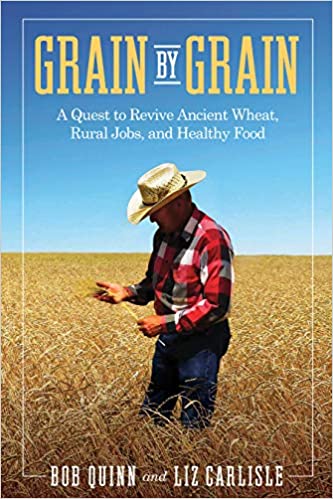

That is very true. I find it weird calling you Bob but I’m still going to call you Bob because it would be weird for me to call you Mr. Quinn. I talked to my husband about this, “Should I call him Mr. Quinn?” I forgot to mention that you have a book out, which I finished reading. I have it on my Kindle but it’s called Grain by Grain. People, you need to read this book. This book is incredible. It’s one of the best books I have read in a very long time. Bob, tell us a little bit more about your path to doing all those amazing things and to being here with us.

I’m glad you mentioned the book because I knew we only had an hour or so. I decided to write a book in case anything got left out. People can pick up the loose ends wherever they want. I was raised here in Big Sandy. When I was in high school, there are 1,000 people in town, now it’s down to 600. My grandfather came here and started our farming ranch in 1920. We celebrated the 100th anniversary of our farm. We still had some opposite observance of the date June 12 of 1920. My father was raised here. I was raised here. I went to the local schools at Big Sandy. I had two great interests in growing up one, was plants. My grandfather showed me how to garden and got me hooked. I love plants anyway. He had got me going in that. Not much after I was walking into the scene. As I’ve got older, science became another great love of mine.

When I went to college, I combined the two at Montana State University and studied Botany and Plant Pathology. I’ve got a BS and a Master’s there. I went on to UC Davis and studied Plant Biochemistry. I was a little bit discouraged with academia when I finished and decided not to pursue that any further. I ended up going a couple of years back on the farm. My whole farm then eventually became a laboratory. I was able to study plants and agricultural systems using all kinds of controls and experiments which I love. I’m still doing that after 40 years on the farm.

When we’ve got back to the farm, my wife and I had three kids already. My parents are still here. It was 2,400 acres. It was big enough for one family but not big enough for two. We started trying to figure out how we could have enough income to survive. I didn’t want to go to town and get a job. I came home to the farm, to my wife and the three kids. They are helping me especially in harvest, seeding, and those sorts of things. We don’t want to buy out our neighbors to get bigger because I like my neighbors. I want to have them around. We didn’t have the means to do that anyway.

We tried to figure out how to add value to what we already had. We started selling our high-protein wheat to whole-grain bakers in California. That was the beginning of opening the door to a whole new era for me. That was direct marketing of what we grew on the farm to those people who were interested in it. We were selling for about $3 a bushel then. They gave us $1 a bushel premium that increased our income by 1/3. That was enough to make the two families survive. That was the beginning of a new road and went on from there, just diverging.

Bob used to come over to our house when I was growing up and my dad was a dry land farmer for many years. That was why he moved to Big Sandy and he was passionate about it. We didn’t have land. He was working for other people. It got him frustrated because they wouldn’t listen. That got a little old after a while. He went on to do some other things. I remember I loved harvest time. I loved being out on the tractor planting. It was an interesting thing. I live in Downtown Los Angeles. I get people all the time, who get on a high horse about farming practices, farmers and ranchers.

Turn your adversaries into friends and work together for common goals. Share on XWhen I was growing up, you would come back to town. When I was coming into my teen years, at that time, the United States had been tapped to feed the world. To do that, people started taking shortcuts from nature. I started reading the story in your book about peaches. We’ve got peaches once for a two-week window a year. They smelled so good. You would spend all two more weeks canning them. You tell the story about going to the peach farm and not being able to smell the peaches.

That was the first time I ever question what we knew as modern agriculture or industrial agriculture. They call it Biotech now and everything else is the latest and greatest. The chemical companies are the ones that are parroting and selling this idea of feeding the world. That’s smoke and mirrors, it’s just marketing. The truth is when the herbicides were first introduced after World War II, I remember my dad saying, “They thought looked at him as a wonder drug.” They had trouble with weeds. They would have to write in front of the combine and poke them into the feeder house with a pitchfork. It’s very dangerous. Did you ever fall into that or anything? It was a challenge to deal with this.

They had moved into this part of Montana with the homesteaders. The homesteaders opened it up from 1914 to 1916 in that era. They found that they could only grow one crop every other year because it was so dry. Their summer followed one year. That means they cultivated the ground to save up the water and then they would grow a cash crop the second year. By the 1940s, there had been 20, 25 years that last from the first homesteaders but only about twelve crops. There hadn’t been much taken out of the soil.

They hadn’t gotten into figuring out good crop rotations or anything like that. It was mostly wheat, winter wheat, spring wheat, barley and some oats. That’s it. Everything was the same. We had two big problems. We had the weed problem and then the fertility of the soil was going down. We are reading the history. It’s so interesting, just as the university’s research centers are starting to study green manures and the effect of legumes on building the soil, a chemical company showed up with this magic fertilizer. All you had to do is to put your drill and scatter it on the field. You didn’t have to plant anything or grow anything new. It took care of that.

You had fertilizers and you had herbicides that solved the weed problem immediately because they work well in the beginning. You had almost an instant acceptance of this and then acceptance became dependent. Things went quite well for 10, 20, 30 years or so and then the telltale signs of the compromise like you were saying. The further you get from nature, the more unstable is the system. This is far from nature.

In the beginning, one of the first things you have and this is the basic of regenerative organic farming, is diversity. If you look at nature, you don’t see any monocultures. Monoculture is an artificial system. To support an artificial system, you have to have crutches and artificial means to support artificial systems. With natural systems, you mimic what’s in nature with natural means. That’s a big difference. With artificial systems, nature tends to react to them. The weeds reacted. They didn’t like to be wiped out every year. They evolved to become resistant to herbicides. This was an unexpected development. What it required was more herbicides, different herbicides and stronger herbicides. It’s a race to the bottom, and it’s more and more expensive all the time. It’s polluting more the environment. That was one of the outcomes.

All the way through college, even in high school that’s what I was taught. When you study plants, you are taught about what they needed and then how to give it to them. You fed them artificially. It’s hard to believe, nowadays, this isn’t done. I had a degree in Botany, which is the study of plants without one requirement for soil class as if plants didn’t grow in soil. Everything was so divided and compartmentalize that you thought, “We are going to solve this farm. We are going to fix the plants the best we can by feeding them and by taking care of them. By treating them with everything they need to protect them from disease and weeds and all this stuff,” without looking at nature. The way nature does it is the soil is alive. It’s feeding the plants and it’s being fed itself. Everything is a big cycle of taking and giving back to the environment in nature. If we farm that way, we will be as successful as nature has been, which is a system that has lasted 1,000s and 10,000s of years. That has some merit of success fee.

People talk about conventional agriculture and they are often referring to chemical agriculture. That’s not conventional agriculture. Conventional agriculture is what we have been doing for 10,000 years. In some parts of the world, they were still doing it and it’s sustainable. What we, you and my neighbors are doing now is a large chemical experiment. It’s about 50 or 60 years old and the wheels are coming off that bus left and right. It’s doomed. The only thing that has a possibility for a future is regenerative organic agriculture where you are renewing the soil. Where you are building the soil and the soil takes care of drawing healthy plants, which then, in turn, makes us healthy.

I’ve got off track because I started telling you that we were taught how we were taught in college. That was how we were being taught and you described well my experience too, growing up with peaches that came in a wooden box and were double wrapped. You set them on the shelf for a couple of days, and they were ripe and wonderful. In California, when I was at Davis, we would go out to the peach orchards that were picking peaches for local consumption. We were going to be canning. College students and graduate students can all our own food that we could. We go out to the peach orchard, and the owner of the orchard said, “Are you planning to can this afternoon or tomorrow?” Based on our answer, he will tell us what boxes to pick from where they are dead ripe and had to go in the jar that afternoon or if they were 1 or 2 days. They would give us something that wasn’t quite as ripe. We get home and they were dripping with juice and wonderful aromas and flavor.

I was on a field trip down the Central Valley and we were going to a big peach farm. They were harvesting. I was quite excited about this because I love to pick tree-ripened peaches off the tree. We’ve got there and I couldn’t smell anything like a ripe peach. We’ve got one and it was hard as a rock. It tasted terrible. It was green and it was still not ripe. Although, it had the appearance of a ripe peach. What we found out later that afternoon is that a professor had developed a petroleum spray that could be sprayed on these peaches as they’ve got near to turning but still were quite green and hard. They would cause the skin to turn that blush color of red or orange that made it look like a ripe peach. They could pick those and they ship them in great big shipping containers that could go clear across the country without any bruising because the peaches were dead green.

When they get to the store, they put them on the shelf. When we’ve got back to Montana, we saw this too. You would buy them, they look beautiful but when you’ve got home, they were hard as a rock. If you let them ripen, they often would rot from the core out so that the inside would start to go bad before the outside was ripe. That was the first time I ever questioned what modern way it goes on the plant and I said, “This isn’t progressing.” It was something that I love negatively and I thought it was false advertising. It looked like something it wasn’t. It would have been created that way or it had been managed that way for marketing purposes, to save money and ship easily across continents. I was still a long way from conversion but it was the first question I had in my mind.

There are a lot that you have talked about in here that I want to come back to because I know some people are going, “Christine you are not talking negotiation as much as you did,” but I’m about to get there. One of the things that I admire about you, Bob, is that you play the entire time I have known you which is a lot of years now, the long game. In negotiation, a lot of people play the short game and they look at what’s in front of them. They negotiate just what’s there and they don’t think about what’s the long-term implication of doing A, B, C or D?

What is interesting is people who are farmers and ranchers are used to have all these long-term views. To your point, it was like 10,000. We have been farming and ranching since our existence for the most part. We have this long-term view and now we’ve got this short-term view. We see the short-term view and I would suggest, especially in the United States and in the Western cultures but it’s becoming more pervasive in other cultures now too. I know you have traveled and been to a lot of places. I have worked in over 50 countries. I have seen it as I have moved across the globe for work. Tell me a little bit about what are some of the challenges that you have encountered having this long-term view, having this vision of what the implications are of these short-term actions? How do you get people to buy into that vision?

I’m in the middle of a whole another campaign that focuses right on what you were saying. It’s not an individual negotiation between two companies. It’s a focus on changing the way we look at the food being a commodity. In our area, people don’t talk about raising food, they talk about raising commodities. Wheat and barley are commodities and they go into the commodity market. I tell whoever wants to listen to me that I don’t raise a single commodity on my whole farm. The only thing I raised is good food. Food that nourishes people, gives them health, vitality and extends their life, that’s what I grow. I don’t grow commodities.

We get into the big discussion of the cost of regenerative organic food because it’s more expensive. There are a lot of good reasons for that. Half my farmer neighbors have gone out of business. I tell people there’s a high cost of cheap food because the goal in this country for the last 50 years has been cheap, plentiful food. We have achieved that goal. There’s a high cost for that cheap food but you don’t pay it at the checkout counter. The farmers pay those who are going broke and can’t farm anymore because they don’t get enough money to pay their bills from the commodity market.

The small communities pay it where half the farmers are gone and they can’t support the mainstream businesses anymore and they start closing up. It’s a vicious cycle. Environment pace, we pay for cleanups and environment. We have a roundup in our array. We have glyphosate. It is using roundup in the rain much of its rate. In Iowa, some of the wells are contaminated with nitrates that children are not allowed to drink from the well. In the Gulf of Mexico, we have a dead area because of chemicals the size of New Jersey, how big does it have to get before we think about it as a problem?

The greatest problem of all is our health. Six out of every ten Americans have at least one chronic disease. Four out of every ten have two or more chronic diseases. Research in the CDC says that 60% of the cause of that is due to the diet that people are on. Much of that goes right to the foot of food, cheap food that fills you up that doesn’t nourish you and doesn’t give you the nutrients you need to stay healthy, to keep your immune system strong and your body functioning properly.

I tell people if you are talking about the price of food, it doesn’t make sense if you only talk about that without connecting it to the cost of health. If you connect those two and you look at what happened many years ago, the sum of those two has hardly changed. It has been about 26% or 27% total of what we spent in households and whatever. What has changed is the cost of food and the cost of health it flipped. 50 or 60 years ago, the cost of food is about 18% of what you spent and the cost of health was around 8% or 9%. Now, that’s the opposite but the total between them is the same.

You cannot talk about one without the other and make sense of it. You can say, “How can we afford to pay more for food?” I said, “How can you afford not to pay more for healthcare?” It doesn’t matter what kind of healthcare system you have. If a significant segment of the population is chronically ill, it doesn’t matter what kind of healthcare system we have, the country is going to be bust. It will not sustain that. We have to look at changing what we are doing and the best way to do it is to start with our food production and how it’s produced. That will drive down the cost of healthcare so we can afford to pay more for food because we are paying only a fraction of that savings for increased costs by reducing the cost of healthcare.

Those are the two things and in negotiation with USC, I had a conversation with the USA and that was the first question I had. I said, “You’ve got to think outside the USA box and include the healthcare box that’s across town from you.” I don’t know where what buildings they are in but you need to talk together. It’s a whole system’s approach and it is necessary. To talk about one is separate from the other is impossible to come to a good solution.

The further you get from nature, the more unstable the system becomes. Share on XIn this quest to redefine how we think about food, I always had this theory as we have built our populations and people have moved off farms and ranches and moved into urban environments. They were not raised around food. They don’t know where their food comes from. They have no idea and it’s through no fault of their own. It’s just they don’t have the opportunity. I live in a concrete jungle, we don’t grow things. I go home to see my folks and then drive around to get to see things but I went home and I love fresh milk. When I say fresh milk to the people who don’t know, I mean fresh-squeezed straight out of the otter, cooled down, cream at the top. That’s the best way to drink it. I still drink it but even the farm has changed.

What’s available in town has changed. The quality of the vegetables and meats in town aren’t what it used to be. Here in Los Angeles and even when we lived in the DC area, in Boston and New York, there are food deserts everywhere. You go into the inner city, they don’t have access to quality food at all. There aren’t many grocery stores. The ones that are there tend to serve fried prepared foods. I know somebody who has a nonprofit that is all about educating elementary school children on how to grow food and she does it through hydroponics because there are not a lot it takes to grow it. When you think about changing this view of what our food is, from a negotiation perspective, it’s what I call a multivariable negotiation. You’ve got politicians on all sides. You’ve got the farming and the ranching community on one side. You have grocers, you have the big manufacturers, the A, B, C, D, and E, or whatever it is. The four guys, Archer-Daniels and all those guys, how do find a thread that connects that? Is that thread the health care discussion? I can see that thread resonating in certain parts of that multivariable, multi-constituent discussion and yet I can see others in that matrix of players not caring about that.

The trouble with the big chemical companies and the Big Pharma is they like everything just the way it is. They don’t want to change anything. If they see something beginning to change, then you can bet your bottom dollar, they will also change and not be left out of the market. The biggest ones will not. If you study history and see what happened to the buggy makers when the cars came in, there are a few that made the transition from buggies to automobiles. Oldsmobile is a notable exception but they are almost gone now.

There weren’t many that saw that change coming and adapted to it. If they will do that, then come on down the doors are open. I’m welcoming you but if they are just going to dig their heels in and say, “We’ve got this, it’s the only way to feed the world. You’ve got to buy our chemicals and if you get sick, don’t worry, we have a pill for you.” This is the mentality and they have no reason to change. They were making billions and billions of dollars. They were sucking up the lifeblood out of rural America especially with the farmers and the small communities.

What we need is more local-based food production. We stated Montana is big. We only need a few acres to feed our million people. We are also depending on exports but we were not feeding our own people. We are focusing on the export, feeding the world and that is breaking us. It’s a failed system. They think that the big government planners and these big guys think, “It’s okay, we are just going to come down with a few giant farms in every county. It doesn’t matter that no one lives there, who would want to live there anyway.” This is the mentality and that’s the thing that we need to change and say that small communities and family-sized farms are important. We need to reintroduce that.

Montana is probably one of the leading wheat-producing states but not producing as much as Kansas, that’s the first one. For organic wheat, we are the biggest producer. If you take the non-organic stuff, it’s like being a boat in the ocean and there’s not a drop to drink. You are surrounded by water and not a drop to drink. There are almost no local mills for buying local flour that’s grown in Montana and the same with the meatpacking. We send our cows out of state to be fattened. We send the cuts back in after they are butchered and we pay the freight both ways, this is insane. We should at least have developed our local food resources and have some food sovereignty and every region of the country could do that and they can produce most of what to eat within 100 miles.

Like blooming in California, I was up in the Central Valley. My daughter surprised me with a trip and took me to wine country and spent the night in Cambria. The almond trees are blooming. There are a huge political thing here in California around water rights and all these kinds of things that come into play. I remember my mom telling me, she was like, “Bob is trying to figure out how to grow apricots or peaches in Montana.”

One of the things that I talked about as a negotiator if you are going to play the long game and no matter what you are doing, there is always a ripple effect. If you are buying a car or a loaf of bread, there’s a ripple effect. You are not going to sit and negotiate in your grocery store about how much you can pay for your bread. I often say that prices should be an output of a negotiation, not a negotiation. Negotiation should not be about price, it should be about all of the elements up and down the supply chain that impact price. That’s where all those assumptions, which in the case for farming and agriculture overall, health is absolutely part of that supply chain.

You are talking about Big Pharma and the big ag businesses and then you were talking about the petroleum-based spray on the peaches. There are a thread that links all of that together. How do you figure out that understanding what that thread is, being well researched and studied to figure out that thread? Figuring out how you plugin and start to unravel it, where do you make digit cuts to the thread and insert an alternative that starts to take over? This is what I have seen you do my whole life ever since I have known you. Big Sandy is called the pioneers. We are Big Sandy pioneers, that’s our team name and you are that person. You pioneered. At a time when I’m sure that there were people in the community who were very opposed to what you were doing.

They thought I was crazy.

I remember some of the stories, you were confident in this different way of doing things and you were curious. I work with a gentleman, one of my mentors is a guy named Blair Dunkley. I mentioned him on almost every episode because I love how he thinks about how the mind works. He talks about getting curious and that’s one of the things that you have done. You are a curious person and you have explored and led you in all these amazing directions. One of the directions, not just on the agricultural side but was on the wind farm component. That’s a great story out of your books too. How you were in Germany meeting and checking out your ancestral heritage and fell into an opportunity. Tell us a little bit about that because I love international negotiations and I love this story because it speaks to being open-minded and curious to find a solution to a bigger problem.

I was in Germany. I was tracking down some of my ancestors and I ended up at a castle in Northern Germany in Friesland, which is quite far North. I knocked on the door and the Count answered. By the end, I had all my records so I can show him how far back I went in this castle and how we were related. He was quite impressed because not many Americans came showing him how they were related, they wanted to see his castle. The castle as you can imagine is a rarity in private hands because there expensive to maintain. If you are going to fix it up and make it energy efficient all that stuff, costs a lot of money.

One thing he had done to maintain this castle habit was built wind turbines. He was right next to the North Sea that had lots of wind and he took me up one. We climbed up the top and he turned it off and turned it on. It’s was great fun. He told me that he and his business partner are looking at other places to build other wind farms because Germany was about to fill up. It was hard to get permits. They were looking at South Africa and Chile.

I said, “You don’t need to go that far. The last time the wind quit blowing in Montana, half the buildings fell.” He got quite a chuckle out of that. He said, “We will come to look,” and they did. In preparing for the trip, another funny thing happened. He said, “My business partner is good, he was such a good engineer. All he has to do is look at the trees and he can tell you about the wind.” I said, “One problem with the Prairie, we don’t have any trees on the Prairie.” It was completely new to them.

They stepped off the plane and I took him to a place where the wind blows all the time called Judith Gap. They have a roadside it says high gusty winds. I said, “Look here, you don’t even need to clear up your wind towers, the highway department is showing you where to build.” We put up towers because they were scientists. We were the first wind park to be taken seriously in Montana and we were competing with many others on a first contract. We lost that competition by being in second place. Being second isn’t satisfying when you want to build something but the person who was in the first place turned out that what he had put together was a lot of smoke and mirrors. It all came apart when they started asking him to put the pen, the paper and making and showing how it’s going to work.

They open it up again and this time, we’ve got first place and then the power company went belly up. We had to be re-organized. We had to bid again, so we won the third time. We won 2 out of 3 of the proposals. The last two are the ones that counted but then we have to go to the state. There are negotiations all over the place. The bird people were all scared to death. I said, “We are going to do whatever you want to give you a comfort level that this isn’t going to be a bird blood bath.” They said, “In some parts of California, it was terrible because they build them in the wrong place.”

We hired engineers to come, we did something never been done before. We had an engineer that did radar at night so they can see how many birds are flying at night. They could count in the daylight but in the nighttime, we don’t know how many are flying around at night. There are a lot of birds that move at night. We took the results from that and we saw a lot of them. This is what hadn’t been done before, we compared it to a wind farm that had also pre-construction data similar to ours and then they had theirs after construction mortality. We were able to extrapolate to what we were expecting.

I was able to demonstrate to our bird-loving friends and I’m one of them too, I love birds that the towers will lose 1 to 1.5 birds per year per tower. The average house car takes out way more than that and so does the average car driving down the road. You were hitting birds, especially if you are in Montana, you are hitting more than once a year, that’s for sure. When we were able to put things in perspective for these folks and they can see that we are serious about studying and seeing as best we could the potential mortality, we were friends with these guys. In my mind, that’s the best form of negotiation, turn your adversaries into friends and work together for common goals. That’s what we were trying to do.

Most of the environmental folks’ common goal was renewable energy. The bird folks were concerned about the cost of that renewable energy. Talking about the cost of cheap food, you have to see what’s behind the curtain to see the whole story. We had to negotiate with the state for the permits and all these things because they didn’t have any permits. They had never been done before. Montana with the expertise of my partners from Germany had been building these things for a long time in developing standards that were reasonable to the extent possible and helpful. To protect the state on one side and not throttle the builders on the other side. That’s always a tightrope and that worked.

We worked through that. We had time because of the negotiations as the actual contracts had fallen through twice. We had quite a bit of time to do all this which took that much time too. It took five years from the time we started to the time it was built. My goal was that Montana’s first wind park wouldn’t be the last one because of all the terrible things that people would say about it and that’s what happened. Now, there are many in Montana and some bigger than the one we built. The one we built was a good size at that time. That was a lot of fun. I had sold my flour mills in Fort Benton. This was about 2000 when it started, I sold that so I had a little bit of free time. I went from one mill to another, I told my friends but the thing that I saw there is a completely clean increment between renewable energy and regenerative organic farming. To me, one smooth right into the other seamlessly. I was comfortable in both of those.

There’s a high cost for cheap food but you don’t pay for it at the checkout counter. Share on XOne of the things for the readers that I hope that you are learning when Bob’s talking is that you have a great deal of clarity in a simplistic pragmatic way of defining what your goals were. We talk a lot, and I talked a lot about getting clear on what it is that you want out of a negotiation and what’s your objective? When I talked about people getting clear, I talked about knowing what you want and what’s important to you but also what’s doable for your counterparts. When you were talking about the bird people, which I’m one too, having an understanding and figuring out, how do we create a solution that allows us to be the first but definitely not the last wind farm? Do what our birding friends need for them to be okay and find what we are doing is acceptable. We are creating goodwill across all of the constituents in the negotiation. A lot of people don’t think about it.

I did a presentation. The woman said at the end of it, she does multi-level marketing. She was like, “I’m not sure how negotiation comes to play in multi-level marketing.” I then did my presentation and she goes, “I learned for the first time that I need to think about my counterpart.” It struck me because my whole world is thinking about it. To me, I always say, “When you are at the negotiation table, you are the least important.” I am the least important person at the table when I’m at the table because it’s all about learning what my counterpart needs and wants. Figuring out, is there a way that we can both get what we want? Is there a way to even create more value than we were both getting more of what we want?

I’m always thinking about my counterparts and that’s what you have done. When you were talking about all of these stories, you were thinking about what is the long game and what are my counterparts need? How do we all become more successful? Negotiation, I always say is a hopeful act. We negotiate with each other because we believe that doing something together is going to have a mutual benefit for both of us that is far greater than if we were not to be doing something together. That’s true when we dissolve relationships too. We believe that the benefit of us not working together is going to be greater than when we do. Talk a little bit more about the thread of connecting renewable energy with regenerative organic farming?

Before we used the word regenerative, we use sustainable a lot when we talk about organic. The same can be applied to energy too. You look at what we are doing now or whatever we are doing. You extend that out, you keep going at the same pace, direction. How many years can you go? How many decades can you go? How many generations can you go? How many centuries can you go? How many millenniums you can go?

Most people don’t think or care about that because they were only going to be here for a few decades. They will be somebody else’s problem. When I look around then I see some of the things that have come down to us from ancient Greece, some of the philosophies and the thinkers, Hippocrates said, “2,300 years ago food should be your medicine, medicines should be your food.” This is a great idea. It has been around for 2,300 years, imagine that. We haven’t paid much attention to it here until recently but still, I would say that’s a long-term vision.

If you were taking coal out of the ground and there’s a bottom to a mine, which there always is. At some point, it’s going to be gone. What are you going to do? Are you going to wait until it’s gone to figure that out or are you going to say, “Maybe we can throttle it back a little bit and still use a little coal but not depend on for everything and let it last longer for one thing?” In the meantime, give us time to develop the alternatives. That’s what renewable energy is in my mind. We are buying ourselves time to get it better and better.

Solar now has surpassed wind as far as its cost and the economics of return of having it. When we were doing our Wind Park years ago, they were about neck and neck. Who knows what would be down the road in developing better wind turbines like better solar cells have been developed in the last years? Those are the exciting things. On our farm are growing high-oleic safflower oil. I started growing that with the idea of going my own fuel and making biodiesel. When I found out all the problems of biodiesel and the reactions that had to be measured and they had to test that and that was expensive, you had wastewater, the glycerin byproducts to deal with and all these things. I’ve got interested in using straight vegetable oil as a replacement for diesel fuel. It couldn’t be used in the winter but we don’t farm in the winter so that’s not a big problem for us. We had to preheat the vegetable oil to 160 degrees and we maintained the diesel tank on the tractor to start it and to get it hot and running. We have an auxiliary tank with the vegetable oil on it and we found out that it worked just fine. You could run all day.

We reduced our carbon footprint immensely by drawing what we were able to put in the fuel tank. What happened to that, however, that got started when it took some of the high-oleic safflower oil to town and gave it to a local restaurant and they said, “It’s the best tasting fried chicken I have ever had.” He said, “I will pay you $2 a pound for this.” If you are doing your Math, it’s not hard to do in your head, 8 pounds per gallon times $2, that’s $16 a gallon. I’m going to put $16 a gallon worth of fuel in my tractor compared to $4 or $5 a gallon for diesel fuel or whatever it was at that time.

That started that idea and we started selling it to the fry houses. We started prescribing all the oil for Montana State University in the University of Montana in Missoula. We had a good relationship when we first started with Missoula and I said, “I would like to get your used oil back and see if we could clean it up and put it in our tractor.” They were willing to work with us to do that. We’ve got our very own oil back. I didn’t want the cheap stuff they’ve got because that was awful about it and everything would screw up the tractor. The straight vegetable oil works fine. All we have to do is take the water out of it and then clean it, filter it. Once that’s filtered, then it would go into the injectors fine.

We preheat it and it ran just fine. We didn’t get involved with this big controversy about raising food or fuel. If we are going to raise food or fuel on our precious acres because we were raising first food and then selling it the second time for fuel. If you can sell any of your crops twice, this improves the bottom line you see. That’s what we are trying to do and we are still experimenting with taking the kinks out of that but it’s a possibility. We don’t have enough to run the cities with this but we have enough for the farms to run themselves. If they all grew safflower, supplied local markets and got all that used oil back and put it into tractors, they could go a long way in fuel and sells everything. That’s the kind of thing where I see the intersection of agriculture and renewable fuels, energy coming right in the focus.

After I read your book, I ordered my Kamut. I ordered the Kracklin’ Kamut, that’s good. I am far more aware of everything. My daughter got something and I was like, “This is all on GMO stuff.” I’m like, “I don’t want to eat it.” It raised my awareness. One of the stories in the book that I liked, Kamut as grain is a special grain. You talked about how in the United States, we have this growing issue around gluten sensitivity. The way that the United States population has dealt with it is to start to cut wheat out of their diet entirely, which is hard to do. That’s the reactionary thing versus saying are the other things, other properties that are driving it and what can we do.

Kamut, because it’s a low gluten grain, what you found was that in Italy market, they were not likely to give up their wheat. You were finding opportunities to sell Kamut there but then you had a question that popped up as you go. I can imagine it popping up in your head going, “Dang it, I’m in Montana and I’m selling my grain in Italy, what does that look like if they were to grow it or if they were to use their local wheat?” There’s a big thing around buy local and all that. You actually took the time and invested to assess what the carbon footprint difference was. To the readers, this goes to understanding the research, what you have, what’s the value that you are creating? Being able to ultimately quantify it but this is an input into that negotiation. Tell us a little bit about what came out of that study and what you found?

I never imagined that I would be contributing to international trade by shipping something as basic as grain across oceans. That was never our goal. We tried to find places in Europe, even in North Africa to grow this grain closer to the markets. I have to make one little technical correction here. Kamut is not the name of the grain. It is a trademark. Trademarks are used to make guarantees to the customers. It’s improper to speak of Kamut as a noun or as a name of a grain.

The name of the grain is Khorasan, it’s a common name like Spelt, Emmer and Einkorn. The Kamut trademark was registered by our family to market this grain and make particular guarantees. The guarantees we make with this grain, if you see the Kamut trademark, you know that it’s always organically grown for one thing. It has never been mixed with any modern wheat, cheap wheat or anything like that. It has always a high protein, high selenium, free of disease and pure.

Those are the promises or the guarantees we make with our trademark. Trademark doesn’t render any ownership with a grain. Anybody can plant it and they can call it whatever they want. If they are going to call it Kamut, they need to be part of our program. If they want to call it whatever, they want to like Khorasan, ancient grain or whatever, they are free to do that. That’s what we have done with that program.

We open ourselves up to criticism by shipping grains across the Atlantic to Europe and they are going by ship. What we found in our study and this is quite amazing to me. I wanted to know if it was possible. This is a long shot, I thought to demonstrate growing grain organically in Alberta Saskatchewan in Montana and shipping across the ocean on a ship that had a carbon footprint bigger or smaller than growing it chemically local.

What we found was, they were almost the same. If we added to that equation, growing it with renewable fuels like my story of the oil then we have a much smaller footprint. It’s amazing to think but the energy cost of going across an ocean on a big ship is negligible because you are taking so much for so little fuel relatively. What the big items are when you take your car and you drive 10 or 20 miles to the grocery store and pick up 1 or 2 items. The amount of energy tabulated to that for a couple of items, a handful or a small sackful, that’s enormous. If you go once a week and you get 4 or 5 boxes that reduce it a lot and if you can shop closer to home. Those are some of the things that people don’t normally think about.

It was surprising that the footprints came out similar to the comparisons we were making. If you look at chemical agriculture with all of the fuel requirements for pesticides, herbicides and especially fertilizers, about 60% of the greenhouse gases coming out of agriculture are coming from chemical fertilizer production. If you eliminate that and are growing your own fertilizers, then that’s a huge plus on that equation. That was what we found. It came up better than we expected. It was an interesting story to share with the customers.

One thing that you mentioned earlier in negotiations and whatnot. When I sat down to visit with folks, I never looked at my suppliers on one hand as suppliers or my customers on the other hand as the customers. I looked at them both as partners that we were in this together and we were going to come up with a program that was beneficial to everybody. We weren’t building our profit on the back of anybody further up the line. It’s because of the trademark, we could dictate a few things. We didn’t allow the manufacturers downstream to build their profits on the back of the farmers upstream. That’s how we held a few extra aces in the deck but that’s how we treat everybody.

Our goal wasn’t to take advantage of everybody either. We have a little carrying charge that made the whole thing work. With that extra money, we paid for about $2 million with the research in Italy with the University of Florence primarily and the University of Bologna, 35 peer-reviewed journal articles trying to understand the difference between modern wheat and ancient wheat that you mentioned. There is a huge difference.

Research says that 60% of what causes chronic diseases is due to the diet that people are on. Share on XThe breeding that we have done over the years to focus on high yields for the farmers, the bakers and creating a bigger loaf of bread has worked. What that has done has changed so much that 20% of the people can no longer eat this modern wheat in America without some difficulty. That was what you were referring to say the quick thing to do. Everybody wants the instant solution while the instant solution is don’t eat any wheat but then you are losing in nutrition.

There was a reason that the foundation of many ancient empires of Egypt, Babylonia, the Greeks or the Romans were all built on wheat. How could it have been that bad all those years and that much success come about? The difference is that the wheat they eat is not the wheat we are eating now. That’s why we didn’t have any idea about that until we started with this ancient wheat. We found out some people just by accident, who couldn’t eat modern wheat could eat this without any trouble and they felt better when they did eat it. After they eat it for a while some of them were less sensitive to other foods so there was a healing thing that we were dealing with. That was a big amazing surprise to us.

My scientific curiosity that you referred to caused me to say, “What? We’ve got to find out what’s going on.” We found out that it was anti-inflammatory. Inflammation is tied to all chronic diseases. Eating this grain reduces your inflammation. It’s going to be a factor in helping reduce or modify chronic disease. That’s huge. Modern wheat aggravates chronic disease, increases inflammation in a small amount and that’s a big difference.

I will tell you what’s driving this, people making more money, if you can have bigger yields, the idea sold to the farmer is you are going to make more money. What they don’t tell you is that they are going to charge you more for your chemicals. You are not making the money, the chemical guys are making the money. Imagine this if you are a baker and you could sell air for the same price as bread. How does that work? That’s a pretty good deal. If you can get less wheat and more bread, that’s what they were interested in. This might be a little bit off but I tell people that have trouble eating wheat and it’s not just gluten. Gluten gets blamed for a lot of things but there are more gluten in the Kamut brand wheat.

What a lot of people don’t realize is with the Kamut Brand wheat, the ancient grain, there are more gluten, a higher percent of gluten and protein than modern wheat in most cases but that gluten is so different. It’s a quality difference, not a quantity difference, it’s important here. The quality is so different that people can eat it without difficulty. If you have trouble eating wheat, there are four things you can do. First, buy only organic then you are not getting any chemical residues that might compromise your health like glyphosate or something like that. Eat only ancient or heirloom wheat. Anything that was on the market before World War II is probably going to be okay or at least better.

Eat whole wheat, don’t eat white refined flour. You are throwing away 1/3 of the best part of the wheat. The pigs are eating better than we are so eat it. The whole grain is good for your digestion, it gives you all kinds of minerals and vitamins that are not in white flour and the right proportions and everything. The fiber is there, it’s important for you and good for your bio gut activity. The final thing is to eat sourdough bread rather than fast-rising yeast. Fast-rising yeast now is very popular. It works so fast that when it’s added to the bread dough, it only has time to digest the sugar that is added which you don’t need to add sugar anyway.

They add sugar and the yeast makes the carbon dioxide to raise the bread, make it nice and white and fluffy and they pop it in the oven. If you ferment that in the sourdough process overnight or 24 hours, not many people do this but if you ferment 48 hours, over 90% of the gluten is destroyed. It’s broken down into simpler components. The digestion is half done before you even eat it. It’s predigested bread essentially, the sourdough if you think it that way. The finishing of that digestion is easy on your system. If you do four of those things, you are probably in a 95% chance that you can enjoy wheat again and enjoy the flavors that didn’t eat tasty treats.

My husband always gives me a hard time because he tells me as a terrible Montana farm girl because I have never been a huge bread eater, pasta eater or anything like that. I don’t know why. I never was but we’ve got a bunch of the Kamut grain, the flour. He’s going to make some bread for me. I’m going to like it.

Try to make sourdough pancakes at least twice a week. They are easy and tasty because you have to remember to do it the night before you have to set those off.

He doesn’t have a starter yet, but so he’s going to come up with a starter.

Let me tell you a quick story about a very negative experience I had or saw with what I call industrial organic. When I first went to Europe, we were working with a company called Lima a leading biodynamic company in Belgium and for all of Europe. They started working with us on our Kamut project, they became our exclusive importer. When I first went there, they took me to meet folks from a small town nearby. They had a fairly good-sized bakery that they were negotiating to buy. This bakery had been in the community for over 130 or 140 years. It was the bread and butter for the community like Big Sandy and maybe 50 to 80 people work there. It’s a big amount for a small town. Several years later, this company, Lima was purchased by a large American organic giant company.

They bought up several of our former customers or partners. After a time, they took an executive decision to close that bakery. It wasn’t because it wasn’t profitable. It was because it wasn’t making enough money. It wasn’t profitable enough. They destroyed the community. They put all those people out of work. They didn’t care less about that. Their bottom line for their quarterly reports wouldn’t have this dragging effect of not being up to the profit percent. That was their goal. That’s the worst type of business when you are focused on the quarterly report to your stockholders. That’s just completely the opposite of how I think. In the short game, you make executive decisions and just cut things that have a big, negative long-term effect. That doesn’t show up on anybody’s bottom line in your company. It’s a big game-changer for the people. You rather work for the companies you shut down or whatever. Those are the opposite of my long-game approach. What I saw right up front, that happened to my friends.

I spent a lot of time working in mergers and acquisitions all over the world. It’s a well-known statistic that almost 75% of mergers fail. It doesn’t work. It rarely works. The merger itself can’t generate the value that is anticipated. It also has ongoing ripple effects that also have long-term negative impacts in many cases. Does that mean you never merge? No, that’s not what it means. For me, when I’m working with clients, You’ve got to get super clear on what the overall objectives are and try to anticipate what these follow on effects are. If he went to the executives of those companies because that company’s massive and owns a lot, it’s the one I’m thinking about from the book that they bought up a lot of small farms. There was a time when they were small farm and somewhere along the way, their values skewed and lost focus of where they were trying to go.

It’s not about you at the negotiation table. It’s not just about the parties at the table. If I’m going to go buy a car, even if my husband is not there, guess what? He’s here. If my daughters or I am going to go do something, my mom’s not there. My mom and dad aren’t there but they are here. We take all of that with us. We always have invisible parties in the negotiation. People that we don’t see that we are not interacting. An effective negotiator pays attention to those silent partners, those people who don’t have a voice at the table. What happens at the table will impact them overall and they need to be considered. I’m glad that you shared that. I appreciate it. How can people find you and tell them more about where to find your book?

You can find the book at any of your favorite bookstores. You can go online and you can find it online anywhere you want to look. It’s also available as audio and in Kindle. If you ever come through Montana, stop in Big Sandy and you can ask anybody where we live, we are about 12 miles out of town SouthEast and I would be happy to sign your book for you. If you want to send it to me, I would be glad to autograph it and send it back to you, it doesn’t matter.

You can find me on the BobQuinnOrganicFarmer.com, Instagram, and the blog which is not so active anymore. You can see some of the historical stuff in it. Kamut.com is our website. You can see our research on that besides local products are. Mostly they were made by other manufacturers throughout the world and there are quite a few in this country. The leading ones are Bob’s Red Mill and Nature’s Path makes cold cereal. You can get the flour and grain from Bob’s Red Mill or most in any store. They are all over. Eden Foods make pasta here in America and lots of different small bakeries are making Kamut bread. They were just scattered around. Those are some of the main things you can find. Good luck. If you have any questions, let us know.

Bob, I am grateful to you to be on the show. For the readers, I hope that you have picked up on some of these important themes from a negotiation perspective, things around playing the long game, things about seeing all the players at the table as your partners and how do you make each other more successful? All of it, not just I’m talking to the supplier and I’m going to make this supplier and me successful and screw the customer. How do I make all of this? How do all the boats rise?

It comes down to negotiating from a position of abundance versus scarcity. Believing that there’s enough in the world for all of us to partake that we can do that. Bob, that’s something that you do. That’s part of your DNA. I can’t imagine you doing anything else. Also, the importance of researching, Bob has a PhD. He loves to research. I’m not a PhD and I also love to research because it’s in the research that we find the solution where we can be creative about problem-solving.

If we don’t care enough about the situation that we are negotiating, about the goal that we are trying to achieve that we don’t research, then we are never going to achieve the goal. It’s in that research where we find those creative solutions to problems. We might unravel something and go, “If I unravel that then that can go here and you figure out how to plug everything together.” I hope that those are some of the things that you guys reading have taken away from this.

Bob, I’m just honored. Thank you so much for being such an incredible role model to me when I was growing up. You did not know the level of influence that you had until we’ve got on the phone. I appreciate you. I appreciate all that you are doing. If there’s anything I can do to help you with that mission, I would love to do that. To the readers, thank you so much for sharing your most precious thing with us and that is your time. We appreciate you doing that. We are honored that you have chosen to do that. Thank you, Bob, I appreciate it.

Thank you. Come and see us next time when you get to the town. Your folks still have the nicest garden all of Big Sandy.

They do love working in it. Thank you very much, Bob. To all the readers, we will see you next time for another episode. Until then, remember that every negotiation is a conversation about a relationship and you cannot win a relationship. Happy negotiating everyone. Until next time. Cheers.

Important Links:

- https://www.Facebook.com/bobquinnorganicfarmer/

- Lima

- BobQuinnOrganicFarmer.com

- Instagram – Bob Quinn Organic Farmer

- Kamut.com

- Bob’s Red Mill

- Nature’s Path

- Eden Foods

- Grain by Grain

- Blair Dunkley

- Episode – Past episode with Blair Dunkley

- Kracklin’ Kamut

About Bob Quinn

Bob Quinn is an organic farmer near Big Sandy, Montana, and a leading green businessman. He served on the first National Organic Standards Board, and has been recognized with the Montana Organic Association Lifetime of Service Award, The Organic Trade Association Organic Leadership Award, and Rodale Institute’s Organic Pioneer Award. His enterprises include the ancient grain business Kamut International and Montana’s first wind farm.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share! https://zone.vennnegotiation.com/