Everybody deserves a decent roof over their head, but sadly, it’s a far reality for some people. Tonja Boykin, the COO at Weingart Center for the Homeless, joins Christine McKay as she shares about solving homelessness, helping communities in need, and the negotiation process that took her there. Having gone to a private school her whole life and teaching in a more affluent community back then, it was a wake-up call for Tonja, realizing that what she experienced growing up wasn’t what others perceived as normal. When she started working on a partnership between the L.A. School District and the mayor’s office back then, it gave Tonja a chance not just to build houses but build communities as well. Tonja shares that although working with government agencies can be difficult, it is well worth seeing how much it means to the people she’s able to help.

—

Watch the episode here

Listen to the podcast here

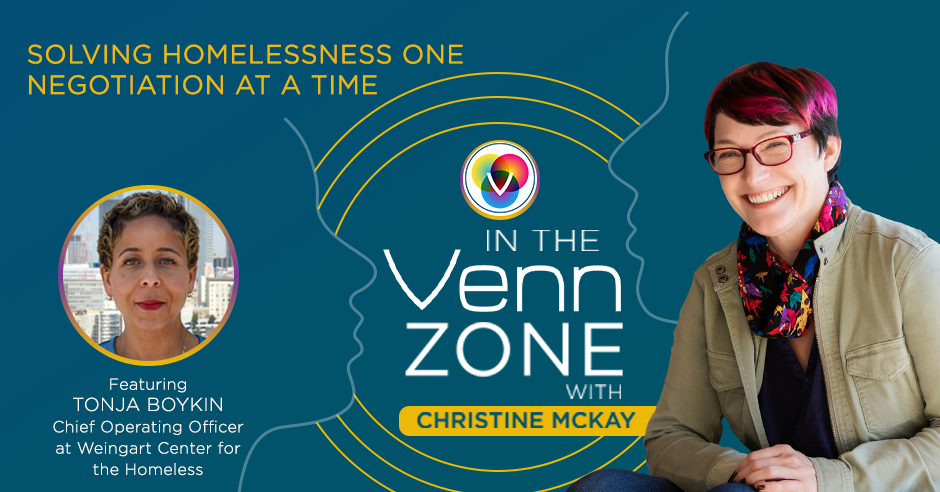

Solving Homelessness One Negotiation At A Time With Tonja Boykin

I am excited to have here with me Tonja Boykin, who is the COO of the Weingart Center here in Los Angeles. She has been in that role since 2016 but she has over 30 years of experience working in various nonprofit organizations throughout the Los Angeles area. She has done an incredible amount of work with the homeless here in the Skid Row area and is passionate about figuring out how to address that issue. We were talking and I was telling her about my episode with Karla Silva. If you haven’t read that episode, check that out.

She does real estate. She was talking about the invisible negotiator at the table and how the community that they’re building in drives a lot of what happens at the negotiation table. We had shared a little bit of that with Tonja and she just lit up like a Christmas tree talking about how negotiating with the community for the work that she does is one of her favorite parts of what she does in her job. I wanted to dig deeper into that conversation to help you understand what that invisible negotiator does and how it influences you. Also, how it manifests itself in the actual negotiation with the people that you’re talking to. Tonja, thank you so much for being here. I am excited to have you. You look gorgeous and lovely as always.

Thank you. It’s so exciting to finally be here. I love what you’re doing and that you’re shining a light on all of those key pieces that make the bigger picture. I’m delighted to be here.

Thank you. I forgot to mention everyone who’s reading this. I was very vague in your bio. Tell us a little bit about the story and how you got to where you’re at as COO of the Weingart Group.

I started my career. I got here in a very roundabout way in my twenties. I was a school teacher. I started teaching school back in the early ‘90s when there was a shortage of teachers. I got called on by a family friend who had been a kindergarten teacher for almost 30 years. She said, “ I think you’d be great at this.” I was teaching in the San Fernando Valley. I’m a Los Angeles native, born and raised and was teaching in a more affluent community. Having gone to private school my whole life. I didn’t think there were any issues.

We had a group of kids. There were perfect class sizes. Kids came to school with the food. They had all the things that I had experienced growing up. When I got her call, she asked me to come to Los Angeles and to teach high school at Morningside High School in Inglewood. I was like a deer in the headlights. Through no-fault a great school and they do their best but I think it’s no surprise that in poor communities, there is a huge gap in what kids in an affluent community are experiencing versus those in more of the inner cities. For me, going into a classroom that had maybe 35 to 40 kids in it, which is a lot, not enough books in the classroom, the conditions of the schools themselves. I had never been in a school where there were holes in the ceiling or kids were sharing books.

Housing is so critical in communities to giving someone the best start they can have in life. Share on XMost importantly, lack of food and not having food. Coming to school, sleepy and without proper clothing. I thought everybody was raised the way I was. I was surprised by that and I was there to teach eleventh grade English and found out that a lot of my students were not able to read well. I took Jack in the Beanstalk as a story for eleventh graders. It may sound crazy but I went to Pacific Oaks College in Pasadena and I’m a whole language teacher. I wrote the book apart. We did science, studying beams in a window. We did the math, counting them. We told stories. We had kids drawing themselves. Anything to engage them, understanding that people learn and listen in very different ways.

While I was doing that, unbeknownst to me, a scout for the mayor’s office was in my classroom during this open house night. I got a call a couple of days later from the mayor’s office. This time, the mayor was Richard Riordan. They said to me. They were starting a program called LA’s BEST Afterschool Enrichment, which was a partnership between the LA School District and the mayor’s office to supplement the regular day schedule in disproportionate communities with programs, science, math, you name it. Would I like to interview for this position to go to schools all over the city and create programs? I got the job, which was exciting and I had the opportunity to be in communities I, quite frankly, never been in before.

Going to Watts, going to parts of South LA, going into the Boyle Heights area and what struck me everywhere I went, I would need to go in and I’d have to listen to the teachers and what their needs were. They were not interested in having a novice come in and do stuff in their classrooms. I talk to parents and kids and find out what they most needed. I then go back to my little desk and created programs. My first set of negotiating skills came from listening to people sometimes, often, not very nice about it. Angry, not angry with me but angry with the system, angry with what was happening in their communities and try to build something out of it. I think that was the first time I understood the power of listening to people in the community and taking their ideas because they’re the ones who lived there and building something that had buy-in, support and would live over time.

While I was doing that, I did that for a couple of years. I’m pleased to say I opened the first site and they opened nineteen more sites while I was there. They are still all over the city, which makes me happy when I see an LA BEST Afterschool Program banner. It makes me proud but then I started to notice that one of the things I saw in all of the communities I went into there was a lack of quality affordable or permanent supportive housing and the impact that that has on everyday life. If you do not have a decent roof over your head and you’re a student, you do not get a good night’s sleep. You are not getting access to good food. You are not getting all the things that we know kids need and people in general to thrive.

If your mom or dad has to get on a bus and go 10 miles just to go to the grocery store, you’re more than likely eating at some convenient shops somewhere and you’re not getting what you need. Housing is so critical in communities to giving someone the best start they can have in life. The reality is we are not on an equitable, even playing field in neighborhoods and communities. I took that knowledge and went to work for an organization called Mercy Housing, which is national and got to go into communities. Not just build housing but listen to the people in the community and find out what they needed. Housing is nothing if you don’t have the buy-in of the folks who are going to live there. If you don’t design programs and services in that housing that they need.

You can’t and I’m sure your previous guest mentioned that you cannot go into a community, plop housing in the middle of it and you wonder why no one’s living there, it gets tagged or it’s derelict. It’s because the community hasn’t embraced it and supported it. Long story short, some years later, I don’t consider myself a housing developer. I don’t consider myself a social services person. I am a community builder. I build and create equitable communities. What we know is when a community has various levels of housing and support systems, the entire community thrives. Where we just have one wealthy area and we don’t have any ladders for people to move up to then that community chokes itself off and dies.

We know that’s what happened with the Fall of Rome is that the disparities between the have and the have not become so great but there’s no middle ground. In many ways, the last year between the pandemic and racial inequities in multiple ways have highlighted that communities and people are not able to survive. I consider myself a community developer, which means I spend a lot of time talking to people about what they need and what they want.

You said a whole lot of things in there. One of the things going back to go a little bit further in the conversation is you were talking about how people listen differently. I talk about listening being a full-body activity. It takes all of your senses. When somebody walks into the room, the perfume they’re wearing communicates something to you or their cologne or they don’t have any. It communicates something. We use our eyes to pick up clues and cues about people that we’re engaging with. When we’re communicating, you don’t necessarily give up who you are as a communicator but you have to meet somebody part way. You got to come out and now we’ve got so many people who are in their corners and trying to stay in their corners.

How’s that serving us? We see it.

It doesn’t serve anybody and when we do that, we’re focused on more scarcity components. It’s just all about me instead of creating something that’s focused on abundance. I love this dialogue around the community and you as a community builder. I’ve known you now for a few years. I’ve seen your evolution and it’s amazing to watch you having grown even further into yourself because Tonja is a dynamo and she’s incredible at what she does. You launched a new project that is huge in Los Angeles. Tell us about that project because I want to dig into some of the negotiation elements that have to do with the community component.

I wish it had a different name but we’re not there yet. It is the Vignes Street Project. It was championed by Supervisor Hilda Solis. It is located right near the men’s prison and Union Station. Everybody knows where the Homeboy’s Industry is. It’s that vacant lot there. It is 4 acres so it’s a big site. It’s 232 beds and a little bit unique. It’s using different models to rapidly house individuals. One hundred of the beds are in the sleeper trailers that have been converted into bedrooms, bathrooms, little kitchenettes and then the 132 beds are in a stacked prefab, modular design and it’s three stories. Also on that campus is a full-scale administration building, a full-scale industrial kitchen, a dog park, lots of green space. We’re laying in all of the trees now and there’ll be some 98 trees which I’m excited about. LA needs more green.

That’s going in and it will house folks coming right off the street. Many are coming from the community surrounding the neighborhood and under the freeway passes. Clients with extremely high acuity, meaning that they have pretty intense mental health issues and with mental health issues they’re typically coupled with substance abuse. We call that dual diagnoses. Because the homeless population is aging, the average age is 55 to 56 years of age. People have been on the street for more than 10 to 15 years. There is a physical component to that as someone who is in her 50s. I get it and could not imagine what happens to the body when it’s on the street. We’re calling it tri-morbids. They’ve got three health factors, mental, physical and substance abuse issues. That’s who we’ll be housing.

The reality is, we are not on an equitable, even playing field in neighborhood communities. Share on XWe’ve started doing intakes. The site is still in construction while we are moving as quickly as we can to take so many blocks. Every time they finished one, we get people in it. We keep them moving through that and it’s been a huge project in terms of negotiation because I have multiple levels. I’ve got the Supervisor’s Office, Supervisor Solis’ team. I have the county CEO’s Office that I need to negotiate with. I have the Council District 14, which is Kevin de Leon. I have community neighbors that have businesses surrounding the area. I have LAHSA, the Los Angeles Homeless Service Agency, that I’m negotiating with as well.

I have the clients themselves that we need to negotiate with because this is all very new for them and they have their own sets of demands. We try to move them from demands to requests and understand the difference between the two. On any given day, I am on multiple calls and multiple meetings. We also have the local BIDs, the Business Improvement District reps and because of where this project is, we have the Chinatown one, we have the Olvera Street Group and we have the folks that are in the Alameda Corridor. We’re managing multiple sets of negotiations, lots of meetings with the goal of which I believe everyone wants, which is creating more housing in the community for those in need.

One of the things that I always think is fascinating about any time you’re working with government agencies, it’s always the level of complexity in those negotiations is significant. Part of that is the political aspect of it. Part of it is the personality of the people who are attracted to that work. What’s the process you go through in starting and initiating engagement with those types of counterparts? How do you initiate that complex level of negotiation?

In the type of work I do, there are two main agreements that we’re trying to get done, which basically drive our ability to run the site before I even get to the community members. With the county CEO’s office, it’s really about the real estate and the licensing agreement, which is pretty intense. To be honest, a lot of the work that the county and providers like myself are doing is brand new. We’re not talking about Measure H dollars. That took a little bit of time to get up and running and we all know have that one under our belts. The new money that’s come out from the government whether it’s FEMA dollars because you’ve got to throw the pandemic in there and their dollars for that. The Federal dollars that are coming through have a prescribed set of agreements and we’ve had to go through those agreements and tweak them as a team.

The way that I typically start off is I gather all the documents that we know we’re going to need to execute. I run through them first and I start to look at where are the things that should stay because they are pertinent to the project we’re working on. What are the things that absolutely shouldn’t be in these boilerplates any longer? I then get down to what are going to be my sticking points and knowing my counterpart at the county, their job is to get this thing executed as well. They’ve got their list of things that they’re not going to move on. It’s really about me getting to know and building a relationship with those individuals early on so that I can get them to tell me what are going to be the things rather subtly that we may do battle on.

In the beginning, I’m sizing up my opponent here. What are the things that we know are going to agree on? Let’s not spend time on that. Let’s get to know each other so I understand their style of negotiation. Hopefully, they give me up a little bit about what may be a sticking point. I do that by going out for drinks or cocktails, meeting at the site and just walking it together so that I both get them to see that I am a real person. Later it’s going to get tough. It happens in every negotiation. It helps if you start with a solid foundation of trust and you got to build that quickly.

Whether it’s grabbing a drink downtown, if they’re located downtown or saying, let’s grab a quick lunch in the pandemic. I’ve done Zoom lunches where it’s like, “I’ll order you salad and have it sent to your office and let’s just talk like, ‘What do you think this project is going to be like? Are we going to be thrilled when it opens? Who’s going to get the coveted role of cutting the red ribbon?’” They seemed silly but they helped me build a rapport with the individual that I’m talking to and when you’re working with the county, it’s a huge agency rate. I may not be working with the person who is the final decision-maker. I want to get comfortable with who that individual is because, at some point, it never fails. I’m going to need to go over their head with permission if we built a good relationship or right away I know it’s going to be a battle. I’m already teeing up talking to their boss, above them, not to backdoor them.

It’s knowing that this is tough stuff and you’ve got lives on the line. Their goal is to make sure that it’s a safe and secure site before they turn it over. I’ve got to look at operating it on a day-to-day basis and sometimes the two conflicts. Starting with a good foundation of getting to know them. I’ve always had good luck with the fact that they’ll give up things. I’ll say something silly, “I didn’t feel about the signage. Where’s the signage going to go on this building?” You would be surprised. People will say, “It has to be here. It can’t have anybody else’s name. It can’t sit anything else.” I never say anything but I know that’s not going to work for me. That’s a little check. I highlight that in the area.

They’ll put something in the document that says you’re going to pay rent. We’re not paying any rent. Why is that in there? Is there a reason for that? I do a little bit of digging. Probably about the third meeting, I start to bullet out the things that I see as a sticking point and I still do it very casually. Here’s the stuff that I think might be a red flag for my boss. What do you think? Should you and I try and hash this out before it goes to the higher-ups? I get really good results that way. Usually, if I’ve done my trust part right, they’ll say, “Tonja, I don’t really care but so-and-so does care about this. Let’s try and negotiate.”

I think I do a lot of one-on-one negotiating before we pull the document out. If I’ve done it well then when we get to the document, there are no surprises. We’ll both be on the phone and say, “Here we go. Are you going to move on this point?” “No, I’m not.” “Are you going to move on this point?” No.” What’s the middle ground. What would work? How do we come to a place where we both feel we’re getting what we want? We’ve met in the middle somehow. Most times, that’s what we come to. There are a couple of pieces at times where we’re just like we’re not going to bend. We’re not going to move.

I don’t want to say it gets ugly but it’s almost like playing chicken. It’s like, “Who’s going to move first?” Are you going to stay on that point? Are you going to move off it? I like to know what my points are right away, that I’m not going to move off of and try to insert them into the conversations on an ongoing basis. I call it my little hypnotism technique because I’ll just keep saying it, “At point 16.1, that’s not changing,” or, “When is that getting removed?” They’ll be like Tonja and then it happens but it’s the way we do to deal with the county.

There are a couple of things that I want to make sure that I highlight. I say this in pretty much every episode because my philosophy of negotiation is that negotiation is a conversation about a relationship. You can not win a relationship but you can get more value out of it. My middle daughter, who’s in her mid-30s, helps me. She does a lot of writing for me. She came up with that. She’s an amazing writer. It’s hugely important when you’re initiating a negotiation conversation because I like what you do. You build a series of yeses and getting, building, accumulating yeses makes it easier to deal with the hard things because every relationship has a hard time.

Housing is nothing if you don’t have the buy-in of the folks who are going to live there. Share on XWhether it’s with your spouse, your best friend, with your pastor or whatever it is. Every relationship that’s worth having has conflict but that accumulating yeses helps you to address that conflict. It builds that trust and you can’t address conflict if you don’t have that trust factor because you’re convinced that your counterpart is not working in your interest and working solely in their own interest. A negotiation is a hopeful act because it means that what you’re doing together is to the greater benefit of everybody involved so that trust is really important. I like how you do it.

I would add one other thing that I do is I do go through the contract and figure out the things that I’m willing to give up. Before I don’t tell them I’m willing to give that up but I have that in my back pocket. Where there are sometimes things that I will say I’m not moving on when secretly, I know, I don’t care and I can give that. Those are my gimmes. I know that there are going to be things that they’re going to want in there. I’ve already assessed is this important to the overall goal? Will this stop the negotiating process? Do I have something in my back pocket that I can say, “If you give me this, I’ll give you this.” so that they do feel to your point that there is a mutual push and pull.

I’m not going to just be hard. I think that what I have learned especially working with governmental agencies is you can only go so far. If you think about the fact that with the county office here in Los Angeles, they’re getting their money from the state. The state’s getting their money from the Federal government and all the way down that line, by the time it gets to us, we’re going to spend that money for construction or programs and services. There are a series of negotiations that have happened. By the time we get to the county level, they’re going to be things that I may not like that I may think are ridiculous. I’m not going to tee my counterpart up for something that they can’t budge on because it is what it is.

There are things that in order to change them, need to go to the legislative level. I don’t want to spend my time beating down, fighting, arguing or whatever word you want to use about something that they can’t change. I can’t change. Later, if we all want to go together to the Capitol and change that rule, it doesn’t help us. It’s helpful to also realize to what you were saying is that it isn’t about the individual themselves. I find that in my career when I have the most difficult time in a negotiation, it’s because the other individual has personalized it. They are thinking that it’s me. I’ve got to make this happen. I tend to look at it like, “Every day, we all go into work. There are just things that we don’t like but we can’t change them. There are certain rules and regulations we have to agree to. Understanding what those are and not spending your time as much as possible on that in the negotiation is also really important.

I love that because one of the things and you and I have talked about this many times in the past that you do that a lot of small business owners and it’s something that always astonishes me, that they don’t read the contracts. They hand them off to an attorney. They trust that their attorney’s going to read them and do the right thing but the attorney doesn’t understand the business in a lot of cases. You end up signing these agreements. You don’t even know what the heck is in them or you get a big company who throws the contract on the table and says, “Sign it. We don’t negotiate.” Many smaller businesses go, “They said they don’t negotiate.” That’s almost universally baloney.

One is the importance of understanding how to read a contract and to know the impact of the contract languages on your business, looking at it, assessing the risk of that specific language and then determining, are there things in here that I can live with? What in here is out of my control as well as out of my counterparts’ control? It is a useless exercise to argue or to get into a conflict over things that neither of you has any control over at all. The other thing that you said that I really appreciated was you said, “Can we do something about it now?” That timing is hugely important because we go into negotiations and it’s like, “Historically, we know we need this so we’re going to negotiate now for something that we think, based on our past experience, we’re going to need in the future.” It’s in a moment thing.

I always tell people I have seen contracts that are many years old. I’m like, “What the heck are you doing?” It’s because that contract is so irrelevant now. They tack on amendment after amendment and it gets sloppy and messy. It’s like, “What the heck is going on?” You’ve got to keep your contract and your negotiated relationships current. You’ve got to keep them relevant. That doesn’t mean you change them every year but you should be re-evaluating your negotiated and contractual relationships every couple of years to make sure if this is still relevant. Business changes so fast that if your contract’s five years old and it goes into an automatic renew, it’s like, “What did you do? Is that contract so relevant? Is it just going to auto-renew because that’s what the contract is?” Don’t put yourself in that trap.

It’s interesting to me. I’ve had the experience with the ladder coming into an organization and it’s like,

“We’re running systems across the street in our main facility. We’ve had these relationships for years and then there’s a change.” We are subject to funding at the state and federal levels. Often, the people who created that contract a few years ago aren’t there anymore. The funding stream has changed and there are different requirements associated with it. I don’t know what the word is. Usually, I’m beating my head up against the wall because I’ve got to go back through the archives and find the original. What was the original intent with this because I’ve got amendment 1, amendment 2, and amendment 363?

It’s like,”I wish they knew Christine,” then we could have just redone this because it doesn’t make sense anymore. No one knows why. They’re usually like, “Sign it. Get it done “ I’m an operational person. I am an implementer. I am 90% implement. “Let’s make it happen.” I feel like my work is done when the project is open. People are on the site. I’m always looking at the paper from how does this play out on the ground? Does this make sense? Most of the time, people get pushed back from me. I think my city and governmental counterparts, I’m known for this is. I’m usually the person on the phone saying, “That doesn’t work. You put this line in here about opening X number of sites in the next twenty days. It’s not going to happen.”

When I first came back to LA a few years ago, LA is probably the most complicated place to get housing done anywhere because the city and county are separate. Unlike San Francisco or Chicago, where they’re together so you’re negotiating with one person. When I came back, I’m looking at these contracts and I’m like, “We’re not going to be able to open X number of units every three days,” and to find out that most of the people on the call who were all brilliant, smart at what they do. They’ve never been on the ground trying to do it. The wording in a contract makes perfect sense to them but then I come along and I’m like, “It doesn’t.” It’s more like XYZ. You got to take that out because at the end of the day. I don’t want to be responsible or sign a document that says I can do something operationally that I know takes longer. Everything’s great on paper until you are dealing with people. When you’re dealing with people, it’s all different.

I was working at a company called Pulse Secure a few years ago. It was a company that was spun off from Juniper Networks and bought by a private equity firm. None of the contracts came with the deal. We had to negotiate new contracts and put new contracts in place with every customer, hundreds and hundreds of customers. I remember I was negotiating with a very large telecommunications company, not in the US. It was a 150-page contract and one clause in that contract they said, “We would agree to adhere to the terms or to the processes and procedures laid out in this 150-page operating manual.”

I was like, “Damn it. That means I got to read this stupid operating manual.” They had prescribed in there things you have to conduct like this type of drug testing on every employee and all of your suppliers and contractors to have to do the same. There were two pages of HR-related things that were procedural and operational things. I set a meeting with the head of HR and said, “How do we do background checks? What is our process for doing background checks? Do we do drug testing? Do we do this? Do we do that?”

You can’t go into a community and plop housing in the middle of it, and you wonder why no one’s living there. Share on XShe’s like, “Why are you asking me all these questions?” I said, “Every major enterprise contract has language in it that dictates what we are supposed to be doing operationally when it comes to how we hire, how we onboard, the training we provide, the annual training that we require employees to go to.” These are language in many contracts. I’m fine agreeing to these things if we do them. If we don’t do them, I’m fine agreeing to them if we understand the cost of implementing these changes and we recover that cost in our price. She’s like, “Christine, I’ve been doing HR. I’ve been in this role in various ways for many years and nobody has ever told me that there are operational implications that are HR-related in a country.

People don’t know. They just sign them.

One of my huge things is operational risk is embedded in every single contract. If you don’t, it’s like sitting down with the people who manage returns. If you have a product, what’s your process for doing a return, for processing a return from beginning to end? How do you replace it? How do you receive it back? How does that happen in inventory? How does the inventory control process work? How do you ship it back out to them? How fast do you have it? What are the contracts you have with the providers who do your shipping? Who’s holding inventory? All of these things matter entering a contract if you don’t understand that process. If you’re not asking for input from the people who understand that process, you’re then contractually obligated to do things you just fundamentally cannot do.

I’ll give you an example. In a contract I was working on, it had listed that because of the pandemic that we would do wellness checks, temperature taking three times a day for over 200 and some people. I get it. I’ve designed a process that we could do that but when it came down to me designing the budget for it, I added the appropriate amount of staff that would be necessary to execute that part of the contract. It was hilarious. The particular agency I was working with came back to me and they said, “We need you to justify your budget.” I said, “Sure, no problem.” “Do you need all of these people?” I then said, “What do you mean? I need all those people.” I am not a person who overloads. We’re a nonprofit. We’re not trying to gouge dollars from the city or state.

They said, “We don’t understand why you need all those people”. I said, “Did you read the operating agreement that you gave to me in your contract? Your contract states that I will do this three times a day, all day long for this many people.” The number of staff that I’ve put in the budget that you are now questioning is a direct result of what you’re telling me I’m required to do. The two individuals on the phone said, “Is that in there? We had no idea.” “It is, on page 24 in big, bold letters it says I have to do this,” but that’s to your point. The staff who put together the contract aren’t reading. That’s not saying I think everyone should do it as you’re pointing up here but they’re used to. They’re a large agency.

They pick up the boilerplate. They stick our name in it. They’re like, “Here, go do it,” because I’m both looking at the dollars, the revenue, the staff, the obligations and the risks involved, I’m also building a budget to mitigate those risks in the price of what I’m going to require as my fee for doing this. I find it so funny and believe me, Christine, it happens in every contract. There’ll be something in it then I put it in the budget and they’ll say to me, “Why do you need that rule?” “Because you told me and I did.” How was I supposed to do what you’re asking me to do? By the way, with the city and governmental contracts, you are audited on a regular basis.

They are auditing your financials, your performance targets and goals and coming to the sites on a daily basis. The folks who wrote the contract are not the people who are going to audit me. The auditors are going to say, “Did you do the wellness checks three times a day? Let me see them.” I can’t then say to them, “The folks down the hall from you said that was no big deal. They didn’t even know it was in there.” It’s a lot of not only reading the contract but I find that I’m educating the people who handed me the contract about what they put in there and the implications because they aren’t following the bouncing ball.

I’ve seen it all the time. Everything from one company we were trying to do a two-year deal. They wanted to do a three-year deal. They sent me a boilerplate contract that had a two-year term on it. They said to me, “We don’t do your deals. We only do three years.” I was like, “You lied.” Another one was like a licensing agreement where it’s like, “We wanted to change our licensing model and we put together a huge analysis on what we wanted it to look like. We just do not do that licensing model,” and sent me a contract that had that licensing model in it.

These things are just sloppy and lazy. The amount of money that you can save by putting on an operational hat and learning how to read a contract in my VennMasters program. We have an exercise to teach people how to read contracts as a layperson, not as an attorney and how to assess what risk it’s affecting so that you can say, “Is that risk worth assuming or not? Do I need to negotiate it?” It’s always astonishing to me when you get the salespeople in companies who are price-focused. Price is an output of a negotiation. It’s not the input. What’s all the stuff that goes into developing price? How does this relationship propose to change that?

There are two things that you said. One, I’m a layperson. I do not have a law background. The way I learned is early on in my career when I went into housing, they just dumped this contract on my desk and said, “Go make this happen.” I’m very nervous and want to do a good job. I’m reading these things and I’m like, “I don’t even know what that means. What does this fiduciary thing mean?” I was surrounded by really great people who I had the opportunity to pick up the phone and call our counsel. Ninety-five percent of the time, our counsel was involved in the actual real estate deal part of it. Not the programmatic delivery part of it. I’d call them and I’d say, “I’ve got this paragraph. What does that mean?”

I got it over time and in fact, when I was with one of my agencies, one of the counsels who also happened to be a board member said, “I had no idea the level of complexity and we’ve never talked about this part.” We spend all our time in the board meeting talking about the real estate deal and the contracts related to that. You’re dealing with complex stuff. She was like, “You’re asking me these questions, show it to me.” I remember scanning it off to her and calling me on the phone going, “What the heck? This is serious.” She started to teach me. “This is what this means. You want to look for this,” even down to getting the insurance that we have to have. Being able to have a conversation with our insurance carriers especially because the work we do is so complex.

There’s not just insuring ourselves, the building and space we’re in but it is sexual harassment, having the right stuff for that because we’re dealing with people both staff and clients. The liability assessments, what people are wearing when they’re on-site if it’s a construction site. All of that is so important. When I read the contract that I am really able to have a good conversation with my insurance carrier to explain it to her because she’s trying to make sure she’s giving us the right level of coverage. Without a deeper conversation and knowing what’s in that contract, we’re going to miss something. We’re going to be exposed in some way. One, I would say to anybody who watches this, if you’re offering a negotiation class for laypeople, they should take it. Mine was just learned over time because I didn’t know you then or I wouldn’t have gone to you.

Everyone deserves a roof over their head, the service and things they need, and the tools to be able to move forward. Share on XThe second thing is most people don’t know what’s in the contracts including the people who are asking you to execute them. They just do not read them. I brought things up on a call and the folks who have handed me the agreement are like, “Is that in there?” “It is. It’s a big red flag.” I got to go ask someone about that because it’s been the same thing over time so I thought those two points that you made were good because I see it every day.

Tonja, how can people find Weingart? How can they find you? I’m excited about elevating nonprofits on my show. I interviewed another organization, too. I want to make sure that we put donation links. How can people get involved?

We are the Weingart Center. You can go to Weingart.org. We are not the foundation. We are a separate agency because we get that all the time. If you go to our website, you will find not only how you can get involved. Right on the front page is a donation link. You can just click the link and donate there. We give different levels. Every dollar counts. We do five for Fridays, $5 goes a long way up to $500,000. If you’re feeling generous, we would love that. Also, we have great stories of our client’s successes and told in their own voices, which you can see. One of the things that’s most exciting to me is we’ve got all of our developments. You can see where we’re building all over the city, the way we’re helping people get housed.

I’m really proud of the work that we do here. You’ll find me on that website. I’m super easy. You can call the Weingart Center or shoot me an email. I would love to talk to anybody who wants to hear about homelessness. The one other thing I’ll say that’s on our website. That’s unique is when I started with the organization, I put up cameras, live video streams. We’re in the epicenter of 6th and San Pedro in Los Angeles and I think homeless people can disassociate themselves from it. If you see it, if you’re able to see it, it’s a 24 hour live cam and you get to see what life is like. I think it’s so compelling and we’ve had great results with people really getting to understand the issue because it can impact any of us.

For people who don’t know my story, I was homeless when I was nineteen so I appreciate the work that you are doing. I was homeless and pregnant so it was six months of lots of unpleasantness.

You are one of those people who is a shining example. I believe that everyone deserves a fair shot. Everyone deserves a decent roof over their head and everyone deserves the services and things they need, the tools to be able to move forward and you are an amazing testimony to that. I am honored to be your friend. I’m so excited about all the work you’re doing.

Thank you so much. You’re amazing. I appreciate you being in my world and in my life. Everyone who’s tuned in, thank you so much for gifting us your most valuable resource, which is your time. We appreciate it. Remember, negotiation is nothing more than a conversation about a relationship and you cannot win a relationship but you can get more value out of it. Happy negotiating. We will see you on the next episode. Thanks. Have a great day. Thanks, Tonja.

Thank you.

Important Links:

- Weingart Center

- Karla Silva – previous episode

- VennMasters

About Tonja Boykin

Tonja Boykin joined the Weingart Center in 2016 to serve as its Chief Operating Officer. Tonja has worked 30 years as a high-performing nonprofit management executive with national and regional expertise in building/optimizing organizational processes, measurement systems, and infrastructure to maximize business results in philanthropy, resident programs and permanent and affordable housing development industries.

She is a skilled strategist who transforms strategic plans into workable solutions and benchmarks performance against key operational targets/goals. Tonja is recognized as a national leader in community organizing, program development and strategic initiatives focused on the hardest to serve populations including families, youth, seniors, and individuals experiencing homelessness or at risk of losing their housing.

Prior to joining the Weingart Center, Tonja served as the Chief Operating Officer for Skid Row Housing Trust and the Regional Director of Philanthropy for Mercy Housing California. Tonja’s career with Mercy Housing began in 2001 and she served in various regional and national capacities throughout her fourteen-year career there. Her early working life began as a program liaison in Mayor Richard Riordan’s office for L.A.’s Best After-School Enrichment program.

She was also a Program Director at the Weingart Urban Center YMCA and a Senior Development Associate at Netzel Associates prior to joining Mercy Housing. In 2020, Ms. Boykin was recognized as one of Los Angeles’s 50 Power Women in Real Estate Development by Bisnow and the recipient of the 2020 Impact-Makers to Watch Award by Stratiscope.

Tonja studied at Pepperdine University in Malibu, California, Pacific Oaks in Pasadena California, and the Fashion Institute Design and Merchandising in Los Angeles, California.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share! https://zone.vennnegotiation.com/